The accusation of “Jewish deicide”—the notion that the Jewish people as a whole bear collective responsibility for the crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth—represents a longstanding anti-semitic trope.

This claim seeks to implicate not only the Jews of first-century Judea but also subsequent generations in a perpetual guilt for the death of Jesus, himself a Jew born and raised in a Jewish context. Rooted in selective and often distorted interpretations of New Testament texts, this fallacy has fueled centuries of prejudice, discrimination, and violence against Jewish communities. However, historical scholarship, biblical analysis, and official statements from major Christian denominations have thoroughly repudiated this myth, emphasizing that Jesus’s execution was carried out by Roman authorities under Pontius Pilate, amid complex socio-political dynamics of the time.

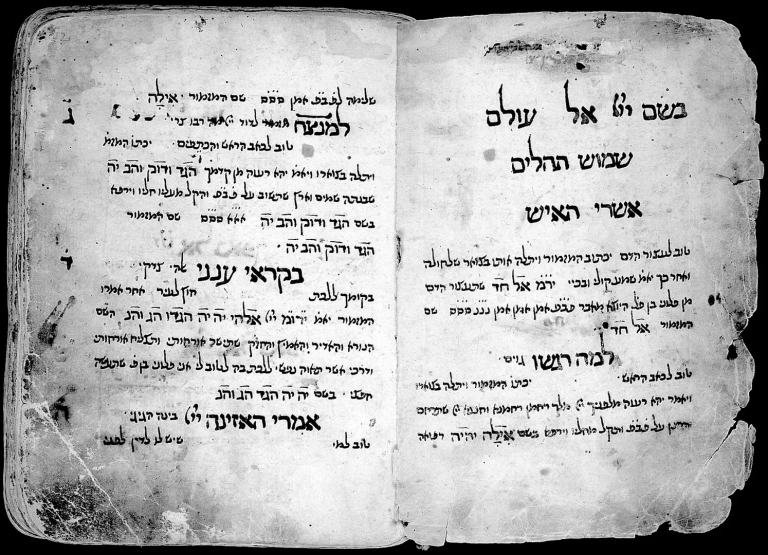

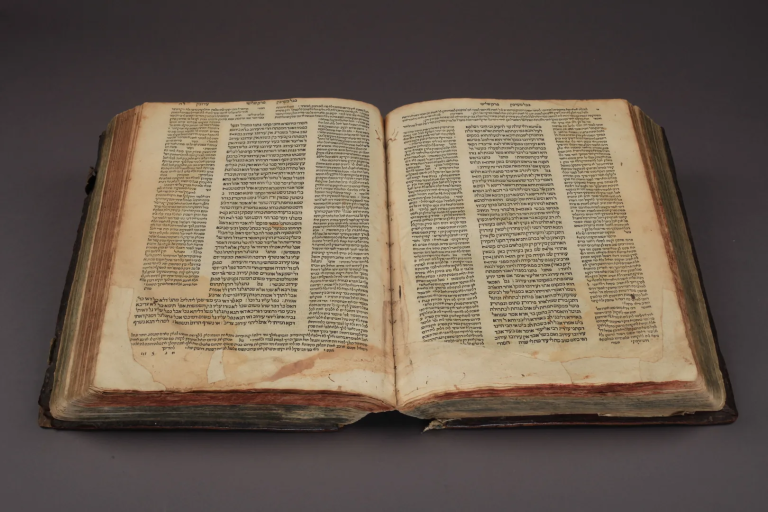

The trope ignores the Jewish identity of Jesus and his earliest followers, nearly all of whom were Jews. The New Testament accounts, such as those in the Gospels, describe Jesus’s betrayal by a single individual, Judas Iscariot (Matthew 26:14-16; Mark 14:10-11; Luke 22:3-6; John 13:21-30), but extend no logical basis for extrapolating this act to the entire Jewish population. Indeed, the Gospels portray Jesus’s ministry as deeply embedded in Jewish traditions, with his disciples and supporters drawn from Jewish circles. The Roman Empire, not Judaism, held ultimate authority over capital punishment in occupied Judea, as evidenced by Pilate’s role in ordering the crucifixion (Matthew 27:11-26; Mark 15:1-15; Luke 23:1-25; John 18:28-19:16). To attribute collective blame to Jews is not only historically inaccurate but also serves to perpetuate antisemitism, as noted by contemporary scholars and religious leaders.

Prominent Christian bodies have explicitly rejected the claim that Jews killed Jesus. The Catholic Church, the world’s largest Christian denomination, addressed it definitively in the Second Vatican Council’s 1965 declaration Nostra Aetate. As articulated in the document, the crucifixion “cannot be charged against all the Jews, without distinction, then alive, nor against the Jews of today.” This milestone statement, promulgated under Pope Paul VI, marked a turning point in Catholic-Jewish relations, condemning antisemitism and affirming the shared spiritual heritage between the two faiths. Drawing from Romans 11:17-24, which likens the Church to branches grafted onto the “good olive” of Israel, Nostra Aetate underscores that Jews remain “dear to God” due to the irrevocable covenants (Romans 11:28-29). The declaration emerged from laborious deliberations, influenced by the horrors of the Holocaust and earlier efforts like the 1947 Seelisberg Conference, which sought to combat anti-Judaism in Christian teaching.

Similarly, Protestant denominations have issued strong repudiations. The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA), in its 1994 “Declaration to the Jewish Community” and subsequent 1998 “Guidelines for Lutheran-Jewish Relations,” explicitly rejects the antisemitic legacy within its tradition, including Martin Luther’s anti-Jewish writings. The Declaration states: “We recognize in anti-Semitism a contradiction and an affront to the Gospel… and we pledge this church to oppose the deadly working of such bigotry.” Point 13 of the Guidelines further instructs: “Lutheran pastors should make it clear in their preaching and teaching that although the New Testament reflects early conflicts, it must not be used as justification for hostility towards present-day Jews. Blame for the death of Jesus should not be attributed to Judaism or the Jewish people, and stereotypes of Judaism as a legalistic religion should be avoided.” These guidelines, adopted by the ELCA Church Council, emphasize mutual respect, shared scriptural roots, and the need for dialogue to heal historical wounds.

The Episcopal Church in the United States echoed this stance in its 1964 General Convention resolution titled “Deicide and the Jews.” The resolution declares: “The General Convention… reject[s] the charge of deicide against the Jews and condemn[s] anti-Semitism.” It further condemns “unchristian accusations against the Jews” and calls for “positive dialogue with appropriate representative bodies of the Jewish Faith.” This action, concurred by the House of Bishops, highlights the role of “loveless attitudes” in perpetuating persecution and urges obedience to the “Law of Love” as central to Christian ethics. Additionally, the Eastern Orthodox Church under Patriarch Metrophanes III stated in 1568 that “injustice… regardless to whoever acted upon or performed against, is still injustice. The unjust person is never relieved of the responsibility of these acts under the pretext that the injustice is done against a heterodox and not to a believer. As our Lord Jesus Christ in the Gospels said do not oppress or accuse anyone falsely; do not make any distinction or give room to the believers to injure those of another belief.”

These ecclesiastical statements align with historical and scholarly consensus. Historians note that Jesus’s trial occurred in a tense Roman-occupied Judea, where political subversion was a Roman concern. Pontius Pilate, as Roman prefect, oversaw the execution. Very few details of Jesus’s crucifixion have been—or even can be—verified as historical fact, and modern interpretations often anachronistically frame the events as a Jewish-Christian conflict, ignoring Christianity’s Jewish origins.

Despite these repudiations, the deicide myth persists in contemporary antisemitism, often resurfacing in extremist rhetoric or during geopolitical tensions. For instance, the ADL documents recent incidents, such as anti-semitic flyers in Macon, Georgia, in October 2023 claiming “every single aspect of Christ’s Crucifixion is Jewish,” or harassment at a Harvard protest in December 2023 where an individual shouted, “You killed Jesus.” In 2022, anti-Zionist author Miko Peled tweeted inflammatory remarks linking the myth to modern politics. Cultural works like Mel Gibson’s 2004 film The Passion of the Christ have also been criticized for reinforcing the trope by depicting Jewish authorities as coercing a reluctant Pilate.

In addressing this myth, it is essential to recognize its role in broader patterns of scapegoating. The Bible itself cautions against such generalizations; Romans 11 warns against arrogance toward the “root” of Israel, affirming that “the gifts and the calling of God are irrevocable” (Romans 11:29). Christian-Jewish dialogue, as promoted in the cited guidelines, fosters understanding and counters prejudice through joint activities like interfaith studies, visits to houses of worship, and educational exchanges.

Ultimately, the question “Did the Jews kill Jesus?” must be answered with a resounding no. The execution was a Roman act, influenced by specific historical circumstances, not a collective Jewish crime. By confronting this trope head-on, drawing on biblical truth and ecclesiastical wisdom, we honor the shared heritage of Abrahamic faiths and work toward a world free from antisemitism. As the ELCA Declaration prays, may there be “continued blessing… upon the increasing cooperation and understanding between Lutheran Christians and Jews”—a sentiment extensible to all who seek justice and reconciliation.

Sources

- Anti-Defamation League. “Antisemitism Uncovered: Myth – Jews Killed Jesus.” Accessed October 7, 2025. https://antisemitism.adl.org/deicide/.

- Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. “Declaration of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America to the Jewish Community.” Adopted April 18, 1994. https://resources.elca.org/wp-content/uploads/Guidelines_For_Lutheran_Jewish_Relations_1998.pdf.

- Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. “Guidelines for Lutheran-Jewish Relations.” Adopted by the ELCA Church Council, November 16, 1998. https://resources.elca.org/wp-content/uploads/Guidelines_For_Lutheran_Jewish_Relations_1998.pdf.

- Fumagalli, Pier Francesco. “Nostra Aetate: A Milestone.” Jubilee 2000 Magazine, November 1, 1997. https://www.vatican.va/jubilee_2000/magazine/documents/ju_mag_01111997_p-31_en.html.

- General Convention of the Episcopal Church. “Deicide and the Jews.” Resolution adopted October 1964. https://www.bc.edu/content/dam/files/research_sites/cjl/texts/cjrelations/resources/documents/protestant/Episcopal_Resolution_1964.htm.

- Papademetriou, Rev. Dr. George C. “An Orthodox Reflection on Truth and Tolerance.” October 14, 1985. https://www.goarch.org/-/an-orthodox-reflection-on-truth-tolerance

- Second Vatican Council. “Nostra Aetate: Declaration on the Relation of the Church to Non-Christian Religions.” Promulgated by Pope Paul VI, October 28, 1965. http://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_decl_19651028_nostra-aetate_en.html.

- World Council of Churches. “Guidelines for Lutheran-Jewish Relations.” Current Dialogue 33, July 1999. http://www.wcc-coe.org/wcc/what/interreligious/cd33-23.html.